A note from Maddy:

It’s always interesting to work with editors and for a platform which are well outside my usual quiet vacuum of independent travails. I submitted this piece to the Washington Post and, because of my editor’s interests as well as the Endangered Species re-listing decision, it became something different.

And here is what I started with, for your consideration:

In late 2020, Coloradans voted by less than one percentage point to reintroduce gray wolves and to charge the state’s Parks and Wildlife Commission (CPW) with creating a plan to bring them back, west of the continental divide. Also known as the Western Slope, this area covers the western third of the state and is home to about 10 percent of its population, myself included.

Approved largely by Front Range (east of the divide) urban and suburban counties, the vote and the mandate it levied are seen by many here as a callous imposition by outsiders, a policy bomb dropped by idealistic urbanites on already-struggling ranching communities.

Approved largely by Front Range (east of the divide) urban and suburban counties, the vote and the mandate it levied are seen by many here as a callous imposition by outsiders, a policy bomb dropped by idealistic urbanites on already-struggling ranching communities.

It’s readymade, culture-war click bait. But to all those with “Coexist” bumper stickers, let’s consider what it really means to move our ecosystem standing from top dog to team player.

Thankfully, while the public rankles and takes sides, many behind the scenes are invested in collaboration and powerful listening. Last year, CPW combed through scores of applications and formed the Stakeholder Advisory Group (SAG), made up of 20 Coloradans who are county commissioners, ranchers, wolf advocates, non-profit administrators, biologists, and outfitters. The state also convened a technical working group, with several veteran wolf experts.

Looking and finding Belle

SAG member Francie Jacober, a Pitkin county commissioner, rancher and teacher, said she believes the group, as well as most Coloradans, are committed to moving forward. “The vote is over. We don’t want to relitigate. And we don’t want to be killing wolves,” she said, referring to developments in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming, where wolf populations have grown and dispersed after being reintroduced in Yellowstone National Park more than 20 years ago. Canis lupus has gone from Endangered Species to hunted, with the years littered with myriad court and legislative battles.

Ideally, when CPW starts the program next year, “they’ll put wolves on the ground and I hope wolves will do what they’re supposed to do, which is to eat deer and elk, and stay out of trouble,” said Adam Gall, a SAG member and licensed outfitter.

As if to challenge this notion, wolves have reintroduced themselves to Colorado, traveling south across the Wyoming state line. In December, in Jackson County, they killed a calf, then a cow, then another cow. At a nearby ranch, they killed Buster, a family dog.

Burro, Wallace, got a scare but escaped with scratches.

“Dog killed by wolf in Colorado” now yields five million search results.

The kills and the exhaustive CPW documentation that followed have taken their toll on these ranching families. Their communities, which voted squarely against the proposition, are reportedly shaken by increased wolf sightings.

For the record, depredation by wolves is rare and the cost is minimal compared to many other categories of loss, like disease or death from a difficult calving. But statistics are cold comfort to ranchers now staying up all night, casting spotlights into the dark to defend herds.

As the 21st century pendulum swings toward re-wilding and righting the wrongs of our ancestors, ranching is caught in a conflicted cultural story arc. We watch ‘Yellowstone,’ but buy turkey meat grown in factory farms or pretend meat grown in labs. We love the Great Wide Open as an idea, not a complicated reality which includes issues around private versus public land, access, recreational use, and the presence of livestock. Livestock is profoundly knitted (until now, mostly lovingly) into our history on this continent. Livestock is cowboys and cowgirls, but it’s also us raising prey animals in environments that require vigilance, stewardship, and resourcefulness.

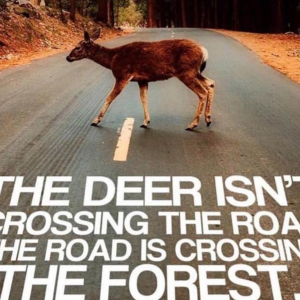

Most folks don’t have daily, intimate, and potentially problematic interactions with wildlife. If a deer collides with your vehicle, or, if a squirrel nests in your garage – you deal with it pragmatically, with solutions like insurance and pest control.

Most folks don’t have daily, intimate, and potentially problematic interactions with wildlife. If a deer collides with your vehicle, or, if a squirrel nests in your garage – you deal with it pragmatically, with solutions like insurance and pest control.

The irony of sides taken in the wolf reintroduction debate (but also in similar contemporary issues, like recreational access to open space) is that coexistence is an idea for one side and a challenging daily reality for the other.

Wolves are beautiful and captivating. So are bears and mountain lions until they shred your pet, keep you up at night, and hurt your wallet.

I lost my dog, Belle, to a mountain lion. We’d headed out for a short hike before dinner. She caught a scent. Belying her 12 years, she bounded up the ridge like a puppy. The cat she’d smelled made quick work of her. When I found her – a dirt-and-snow colored dog, laying stone-cold in dirt and snow – those big brown eyes were still open.

It was also a lion that left claw marks on each side of my donkey’s haunches, having tried and failed to take him down.

Lion tracks by my house

Jacober, who has lived and ranched in Colorado for years, said she’s terrified at the thought of encountering a pack of wolves in the backcountry. “But it gets to the core idea of what it means to be human,” she said.

If we are indeed shifting to an all-inclusive ecological mindset, it would be nice for those lacking immediate, daily interactions to better understand the practical realities of wildness and coexistence.

Wolves spur us to “consider our humanity and our place on this landscape in a way that other animals don’t,” said SAG member Matt Barnes. If we are team players, “then we should make room for other species, at least where we can,” he said. That won’t happen in downtown DC, but what if it did?

Rest in peace, Belle