Editor’s Note:

A version of this essay was published in the Washington Post.

Maddy Butcher writes:

Few friends aren’t going through something now. It might be relationship struggles or tough times at work. It is often a mental health deal. Sometimes it’s a blend of existential worry, family matters, substance overuse, and climate concerns, all mashed together. According to the US Census, 42 percent of Americans reported symptoms of anxiety or depression late last year.

If the 2016 election unearthed deep societal ills, then the pandemic has exposed the delicate, dysfunctional nature of 21st century American existence.

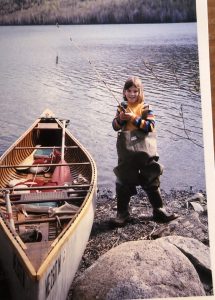

The author circa 1974

Grappling with uncertainties, I believe we reach for comfort and novelty in equal measure. This summer, one of record-setting road-tripping and outdoor recreating, I reached for a totem of both security and adventure. I grasped for a wanigan.

My dad made one in the 1960’s. Bigger than a microwave and smaller than a hay bale, it was a bulky box for equipment and groceries. Built of quarter-inch plywood, with metal handles and a hinged top that doubled as a small table, it was a beloved family unit serving three generations of campers. It carried cups, plates, pots, cans of corned beef hash, and cookies.

We took ours down the St. John, Penobscot, and Allagash Rivers. Like the Allagash and Penobscot, the wanigan is a Native American word meaning ‘storage container.’ As a girl, though, I heard “want-again.” because whatever you put inside, you’d soon want again.

This summer, I wanted desperately to find the old wooden beast and put it back into action for camping in the Rockies. But it was gone, reported my father. Maybe it didn’t survive my parents’ move from country home to in-town condo. Hard saying with older folks and long-distance communication.

Dad offered to construct another one. Over calls and emails. we nailed down dimensions and materials. Three weeks later, a large, heavy box arrived via US mail, containing the disassembled plywood, old prescription bottles full of screws, and a home-printed set of instructions. With celebratory beer and music, I put it together that night, emblazoned it with my initials, and varnished it the next day.

Dad offered to construct another one. Over calls and emails. we nailed down dimensions and materials. Three weeks later, a large, heavy box arrived via US mail, containing the disassembled plywood, old prescription bottles full of screws, and a home-printed set of instructions. With celebratory beer and music, I put it together that night, emblazoned it with my initials, and varnished it the next day.

I packed it with one bowl, one pot, one mug, a set of utensils, matches, tea, Oreos, nuts, soup, ramen, boxed milk, Grapenuts, and bananas. I hefted it across the dirt driveway and placed it in my horse trailer along with my saddles, saddle pads, headstalls, sleeping bag, camp stove, and East of Eden by John Steinbeck.

I loaded up two horses, three dogs, and headed to Creede, Colorado, to help a friend with cattle.

Like so many small mountain towns, Creede is swollen with out-of-towners lately. It hosts some 4,000 seasonal visitors, who cramp and support about 300 permanent residents. Tourists crowd narrow streets with expansive RVs and late model Jeeps.

Others camp quietly, almost invisibly, on the surrounding 1.83 million acres of the Rio Grande National Forest. They are passing through and getting by.

There is Arnie, who is sleeping in the back of his Toyota truck and enjoys port wine from time to time. Arnie paints beautiful signs for businesses around town and will head back to California, he says, when it starts getting cold.

Fishing in Creede

There is Jess, who is living out of her horse trailer and bathing in the ice-cold Middle Creek. She’s recently divorced and tells me everything she owns is in her Dodge and her stock trailer.

At first light, not far from Middle Creek, I reach inside the wanigan and smell its new coat of varnish. It reminds me of a family trip on the St. John which started with two days of solid rain. We didn’t take a lot of vacations together and they would not be canceled on account of weather. On the first night, I slept in an old campground outhouse rather than a flooded tent. The river rose more than a foot and the next day, in our wide, old-fashioned canoes, we white-knuckled it through rapids made enormous by the rains.

Some forty years along, I grab a pot and boil water for tea, then use the same pot for hot cereal. The sun burns off low-lying mist around Bristol Head, elevation, 12,713 feet. Later, I ride and work with my Border collies over 20 miles of high country, urging cows to new pasture with my friend.

Working cows across the Rio Grande

The pandemic has me embracing a new normal in which suffering and good times sit more cozily side by side, like the jumble of a wanigan. Animals I care for get hurt and die. My grandbaby was born to great joy coupled with worry. Money comes and then goes.

I consider Steinbeck, who wrote “The Irish do have a despairing quality of gaiety, but they have also a dour and brooding ghost that rides on their shoulders and peers in on their thoughts.”

When Covid finally recedes, perhaps we may indeed purge ourselves of sadness and anxiety. More likely, I think, we’ll carry them with us as relics of the pandemic journey.