Sam Perry, co-owner of Fenceline Cider, in Mancos, was a studio art major in college. So, it makes sense that he’d reference a color palette when describing the narrowness of cider flavors ‘round here.

Sam Perry, co-owner of Fenceline Cider, in Mancos, was a studio art major in college. So, it makes sense that he’d reference a color palette when describing the narrowness of cider flavors ‘round here.

Despite the wealth of apple varieties, “we’ve been painting with brown,” said Perry.

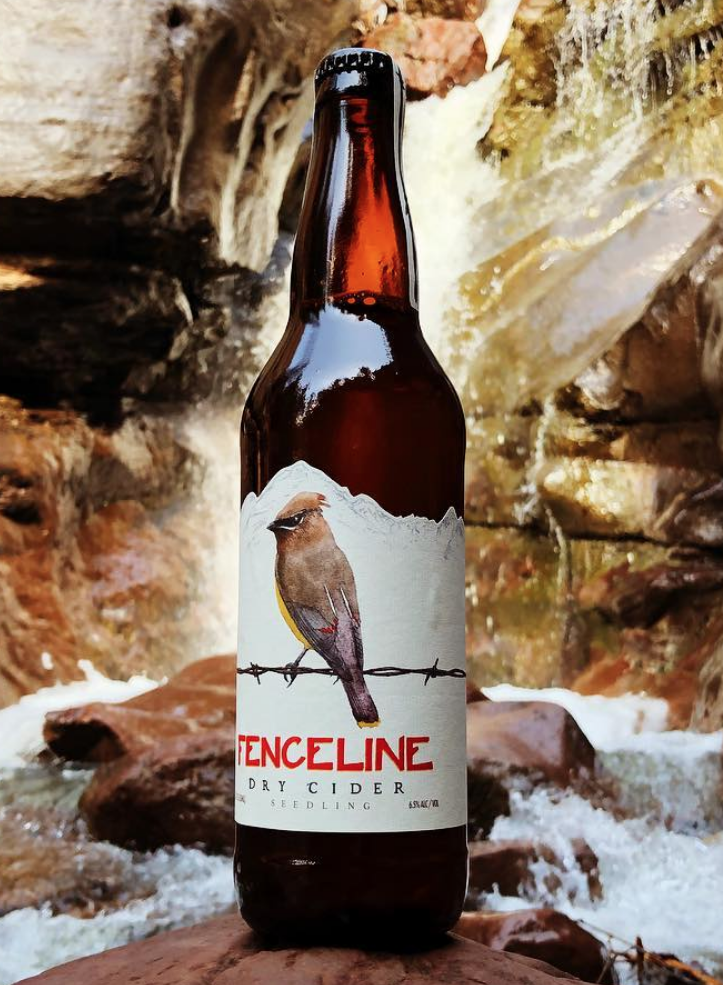

Fenceline, part of Outlier Cellars, wants to expand the palette and, in the process, get customers to step up their cider savvy.

At a time when you can’t bend an elbow without bumping into yet another craft brewer and yet another beer drinker who’s all about hop assemblage and IBU ratings, cider – made from local apples and served at a sweet, riverside tasting room – seems pretty darn refreshing.

Outlier Cellars is the new company owned by Perry and Neal Wight. I sat down with them recently to chat about the part of apples and their business that intrigued me the most: fencelines.

Without putting forth a dissertation on apple science, it’s nonetheless relevant to appreciate that the fruit’s genetics are funny. Genetically speaking, apples do fall far from the tree.

“It’s pretty much impossible for a Fuji apple seed from a Fuji apple tree to grow to be the same,” said Wight. “It might have similar traits, but it won’t be the same.”

That’s why commercial fruit from orchards worldwide are nearly entirely grafted stock. Grafting is how apple growers select for traits. Planting seeds is not.

When Perry and Wight started researching years ago, they’d drive around the Montezuma County, checking out old orchards.

Sam Perry (top) and Neal Wight celebrate a recent harvest

“But what we discovered very quickly was the most interesting apple varieties grew right outside of the orchards, along the fencelines,” said Perry.

Typically, birds feed on orchard apples. Perch on the fence. Poop seed. The fittest/strongest/luckiest seeds grow into trees and bear fruit. These trees, by their very nature, are resilient. They aren’t nurtured or protected by anyone or anything other than their fenceline status (which means they are less likely to be mowed down, for instance). Call it affectionate neglect.

The pair tasted and rated apples from scores of untended trees for tannin, acidity, sweetness, pick-ability, and size. They got in touch with land owners and asked for permission to take cuttings. Most folks were excited that someone was interested in the fruit from their untended trees, said Perry.

One of his favorite trees is along rancher Tom Weaver’s fenceline, near the Mormon church on Montezuma Street in Mancos.

“I called him up and said, ‘hey, you’ve got this cool cider tree. Can I take some cuttings?’ He said, ‘sure.’” Perry now has many trees on which are grafted fenceline cuttings. In time, these will bear some intensely provincial cider.

On his 90-acre Mancos property, the Outlier crew nurtures some 600 trees on five acres. When fully mature, they will harvest four to five tons of fruit per acre. Six months after a harvest, you’ll have a glass of very special Mancos cider.

“We’ll eventually be making ciders with fruit that no one else has access to. It’s unique to this region,” said Perry, who may steadily convert more pasture ground to orchard.

Will us cider drinkers step up to the challenge and learn to appreciate Fenceline nuance? It could be a pretty delicious task.

The tasting room sits along the Mancos River in Mancos